The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy says that ethics is the philosophical study of morality. But the word ethics also sometimes substitutes for the moral principles of an individual, group, or culture. In that second sense, ethics and ethical questions are one way to look at structuring our own biography. For me, for instance, there have been key questions (and answers) that mark stages in my life. Questions about the rights of women, questions about ecology, questions about animal rights, and questions about the rights of homosexuals have been key issues in my life. At a very personal level, these questions have been preoccupations at different points in my life. Ethical questions have also structured the way I analyze historical periods and personalities. They have framed my universe.

Given the little I know about the life of Einstein, this was true for him as well. Yes, the scientific research and breakthroughs are one way to set boundaries to periods of his life. But another way to look at his life concerns ethical and political issues, one of the key questions being the treatment of Jews.

According to Robert Schulman’s lecture this morning at EinsteinFest, Einstein Recovers Judaism and Discovers Politics, Einstein’s recovery of an appreciation for his Jewishness (cultural Judaism) led directly to his political involvement in later life. Until 1919, when Einstein was thrust into international stardom, he cared little for Judaism (there was a brief boyhood fling with religious Judaism). He considered himself part of the international community of scientists, someone who was “unaffiliated” with any specific religion, except when required to pretend that he had a religious background (Kaiser Franz Josef had declared that no atheist was to hold any position in the empire’s civil service).

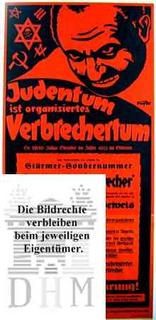

This all changed after 1919. His “moratorium as a Jew” ended with his high public profile and his discovery of anti-Semitism, especially against eastern European Jews in Germany. He embraced cultural Zionism and focused much of his political involvement from 1919 to 1948, when the state of Israel was created, on fighting both Gentile and Jewish anti-Semitism (the latter was the worst possible form of anti-Semitism in Einstein’s eyes).

Einstein compromised his strategies, but never his principles. After the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, he set aside his pacifism temporarily because of the fascist threat. Again, the more I learn about him, the more inspired I am by his example.

No comments:

Post a Comment