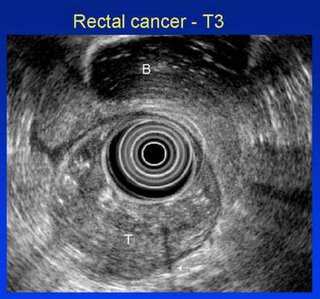

As 2005 closes with a diagnosis of rectal cancer, 2006 approaches with the prospect of chemoradiotherapy, surgery and more chemotherapy. All treatments are important, but surgery is clearly the most invasive and possibly curative of the three. I turn my attention to the intention of my surgical oncologist to use a technique called TME or total mesorectal excision. My academic training as an historian sometimes affects how I conduct research into important issues in my life. Here is what I’ve found about surgical techniques for rectal cancer. (Much of what follows comes directly from the article The Role of Total Mesorectal Excision in the Management of Rectal Cancer, published in 2002.)

Early Treatment

Ernest Miles first described abdominoperineal resection in 1908 (abdominoperineal resection is a surgical procedure in which both the rectum and the anus are removed from the patient, thereby requiring a colostomy, an opening in the abdominal wall by which to connect the remaining colon and replace the anus; the patient is thereby left with a device for the remainder of his life to handle defecation). By the 1920s, this surgical method had reduced rates of recurrence of rectal cancer from almost 100% to about 30%. The practice became the gold standard for surgical treatment of rectal cancer for many years even though there were still significant recurrence rates and urinary, sexual and gastrointestinal side-effects.

Mid-Century Treatment

By the 1950s, anterior resection (a portion of the rectum is removed and the remaining ends are joined) replaced abdominoperineal resection as the surgical standard treatment for rectal cancer. One of the distinct advantages for patients in this approach was the possibility of avoiding a colostomy. Unfortunately, there continued to be significant concern about recurrence rates.

Current Treatment

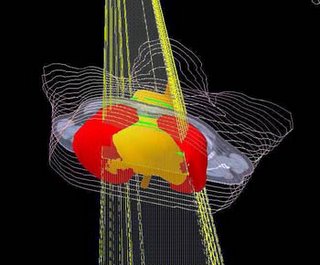

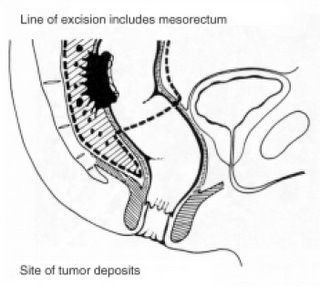

Then, in 1982, total mesorectal excision was first described by RJ Heald and his colleagues. The TME procedure is based on complete removal of the mesorectum, the tumour and as much of the rectal tissue as necessary. The mesorectum is the rectal mesentery, a membranous fold of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes and fatty tissue which is itself contained within a thin membrane called the mesorectal fascia containing the rectum, the mesorectum and the lymph nodes. A major goal of TME surgery is to remove the mesorectum intact. Why? Because the blood supply and lymphatic drainage for the rectum are contained in the mesorectum. If the mesorectum is removed, the chances of cancer cells spilling during surgery and remaining in the abdominal region are greatly reduced. TME has been shown to reduce rates of recurrence to as low as 4% after 5 years from the time of curative surgery.

Now, TME is considered the gold standard for surgical treatment of middle and lower-third rectal cancer in most of Europe, with many advocates in the United States and Canada. But the technique is difficult and requires great skill on the part of the surgeon conducting the 3- to 5-hour procedure. In fact, of all major surgically treated cancers, outcomes for rectal cancer treated with TME are the most dependent on the technical skills and experience of the surgical oncologist.

Monitoring Skill Level

Heald recommended an audit method for surgeons utilizing TME techniques. It is called the Quirke-based method for histopathological study of the excised specimen. Dr Phil Quirke promoted the circumferential margin involvement (CMI) of the TME specimen as a significant indicator of local recurrence of cancer. In other words, the pathologist has to examine the circumference of the specimen very carefully to determine how far from the outer edge of the specimen cancer cells are located. Generally, if there is a margin of 1 mm for the entire circumference, then it is designated as “clear”. In addition, the pathologist has to assess 12 or more lymph nodes to ensure there are no metastases of the cancer.

Standardization of both terminology and technique is progressing. As of 1999, surgical oncologists agreed to dispense with other names for the surgical technique and agreed to settle on TME. In Canada, it appears that at least some provinces are moving towards standardizing on Quirke-method histopathology techniques thereby allowing better evaluation of surgical expertise.

Problems

There continue to be problems with TME for the patient. Leakage rates from the anastomatic resection and the inability to defer defecation in lower rectal resections, especially in lower rectal resections, continue to be problematic. If nerve-sparing techniques are utilized in TME, there is mounting evidence that urinary and sexual function can be spared, but patients should be prepared psychologically for potential problems.

Future Directions

Laparoscopic surgical techniques for total mesorectal excisions may become more common. A study from 2001 assessed open surgery and laparoscopic-assisted surgery (far smaller incisions for the patient); in that study, it was estimated that up to 50% of patients would benefit without compromising survival and recurrence rates. Another presentation by Michelle K. Smith at the 8th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery in which 112 consecutive patients in 3 centres in France from 1991 to 2001 were treated with laparoscopic TME suggests that laparoscopic TME may even be superior to open surgery insofar as there is improved visualization, it is easier to determine correct anatomical planes, and there is improved ability to standardize and teach the technique to other surgical oncologists.